Incoming data for H2.17 is evidencing that while sub -Saharan Africa continues to experience subdued growth on the commodity price effect, globally economic activity is picking up, but structural impediments in many sub-Saharan countries, South Africa included, will limit the lift gained from the (modest) global upswing. While commodity prices have recovered to some extent, many commodity exporters are reported to be finding commodity price levels still insufficient and government debt levels have been rising, particularly in sub-Saharan countries where this has increased uncertainty and so negatively impacted investment.

South Africa suffered from a contraction in investment last year (2016), and government gross debt has escalated from 22% of GDP in 2008/09 to 45.7% of GDP in 2016/17. Uncertainty has risen too on the political and economic policy front with South Africa currently seeing its key credit ratings split between investment grade (IG) and sub-investment grade (SG). Moody’s and S&P have South Africa local currency (LC) long-term sovereign debt (LSD) on investment grade, while Fitch has it on sub-investment grade. South Africa’s foreign currency (FC) long-term sovereign debt is investment grade from only Moody’s, while Fitch and S&P have it on sub-investment grade. This three/three split will likely persist after Moody’s country review of South Africa, as the agency is expected to move its local currency and foreign currency long-term sovereign debt ratings down by only one notch (still investment grade). South Africa bonds would then not fall out of the World Government Bond Index (WGBI), with likely little further impact on the rand from this source this year. However, with country reviews from Fitch and S&P twice a year at least, and the possibility of ratings changes between scheduled reviews, the possibility of further downgrades cannot be excluded, which has heightened uncertainty. A 35% weighting is ascribed to this down case of further credit rating downgrades and a 35% weighting to the expected case. With the World Government Bond Index holding a large amount of South Africa’s LC (local currency) LSD (long-term sovereign debt) the rand could weaken substantially if this Citibank fund has to sell its South African bonds (local currency long-term sovereign debt), given the large size of its holdings. The rand and bond yields were to a significant extent shielded from April’s credit rating downgrades by the strong risk on financial markets as foreign investors were heavy purchasers of Emerging Market debt globally. Looking forward for the rand much will depend on the global cycle, with the domestic currency at high risk of volatility, and weakness in particular from further credit rating downgrades and/or a risk-off global environment.

Expansionary fiscal policy in the US is still expected to drive growth, while the European recovery continues, with manufacturing activity and trade improvements of 2016 still noted globally, and indications that this persisted into H2.17. The feed through into investment and imports is expected to persist, strengthening global economic activity. However the slowdown in China and moderation in commodity prices has impacted emerging market growth, with only a modest pick-up expected. In sub-Saharan Africa a lift in growth is expected as well (see figure 2), with South Africa’s pick-up in growth more modest. Commodity prices are generally expected to rise this year and next, but only modestly, and not reaching the heights of 2011 (see figure 4).

In this modest global growth environment, with only a gentle upward trend in commodity prices, commodity exporters cannot expect a substantial boost to economic growth from this source. Rising government debt levels will need to be reined in, with South Africa receiving a credit rating downgrade this year on its escalation in debt to GDP since 2009 in a declining growth environment (with substantial contingent liabilities on its balance sheet from the guarantees to its state owned entities). The credit rating downgrade is not expected to precipitate an interest rate hike this year, with the impact on the rand and bonds proving limited in the global risk-on period. The Forward Rate Agreement curve is flat to down this year while the US is expected to hike by two to three 25bp increments in 2017. CPI inflation is expected to moderate in South Africa this year, and next year as food prices moderate and demand pressures remain weak in the economy as economic growth remains below trend until 2022.

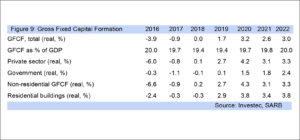

The fall in fixed investment (Gross fixed capital formation) in South Africa in 2016 (see figure 9) was driven by state owned entities and the private sector, with growth in government investment slowing down sharply. The IMF says “rising public sector debt is becoming a cause for concern in sub-Saharan Africa …the ratio of public debt to GDP has increased …to an average of 42 percent of GDP in 2016 (and a median of 51 percent). This is the highest value since many countries received debt relief in the 2000s under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries/Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative.” South Africa’s fiscal constraints have led to lower investment growth for government and State Owned Enterprises, with the bulk of state expenditure focused on social services and civil servant remuneration, while the country continues to run a primary deficit. At 46% of GDP South Africa’s debt to GDP ratio is similar to the debt to GDP ratio inherited by the ANC tripartite alliance in 1994 with the advent of democracy, when the fiscal deficit for national government was close to 7% of GDP. At that time South Africa’s credit ratings were sub-investment grade. The IMF notes “prudent fiscal policies play a special role in sustaining growth .

The fall in fixed investment (Gross fixed capital formation) in South Africa in 2016 (see figure 9) was driven by state owned entities and the private sector, with growth in government investment slowing down sharply. The IMF says “rising public sector debt is becoming a cause for concern in sub-Saharan Africa …the ratio of public debt to GDP has increased …to an average of 42 percent of GDP in 2016 (and a median of 51 percent). This is the highest value since many countries received debt relief in the 2000s under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries/Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative.” South Africa’s fiscal constraints have led to lower investment growth for government and State Owned Enterprises, with the bulk of state expenditure focused on social services and civil servant remuneration, while the country continues to run a primary deficit. At 46% of GDP South Africa’s debt to GDP ratio is similar to the debt to GDP ratio inherited by the ANC tripartite alliance in 1994 with the advent of democracy, when the fiscal deficit for national government was close to 7% of GDP. At that time South Africa’s credit ratings were sub-investment grade. The IMF notes “prudent fiscal policies play a special role in sustaining growth .

Spells in sub-Saharan Africa: a better fiscal balance significantly increases the chance that a growth spell will continue, while conversely, a higher debt burden can accelerate its end. …in particular …a lower debt-to-GDP ratio tend to prolong growth spells in the (sub-Saharan African) region.” The IMF adds currently that “weakening commodity exports, the ensuing sharp slowdown in economic activity, and the build-up of government payment arrears to contractors are all restricting private firms’ capacity to service their loans to various degrees across the region.”

Business confidence has essentially remained at depressed levels since 2009, with an average of 59% of business dissatisfied with business conditions. The close link to fixed investment has shown a contraction in private sector investment over the period. Heightened uncertainty, reflected in poor confidence levels leads to lack of investor appetite, as does anaemic domestic demand. Industrial production is expected to be weak, but positive over the forecast period of 2017 to 2021. Consumer confidence has been very weak over the period, with gross national income per capita falling in real terms in 2016, both of which have subdued real household consumption expenditure (HCE), and so GDP growth.

With Moody’s still to review South Africa’s country credit local currency and foreign currency ratings, but likely to keep them investment grade, it will be December’s country reviews which could have a ratings impact on the rand, unless further political disturbances this year promote another round of downgrades. A more gradual trajectory than previously is likely in the return to PPP, given the recent downward trend in credit ratings. The rand could therefore reach PPP in 2020, where PPP valuation will then be closer to R11.50/USD. Loss of another investment grade local currency long-term sovereign credit rating would delay the return to PPP further, while loss of all investment grade local currency long-term sovereign credit ratings would mean the rand would be unlikely to return to PPP. Unless otherwise stated all views in this narrative are of the baseline case.

South Africa has lost growth momentum, with the economy in a downward growth trend over the past several years. Economic growth of around 1.0% y/y is insufficient to prevent further credit rating downgrades, particularly if government debt to GDP ratios does not fall and there is insufficient State Owned Enterprise reform. The agencies also point to concerns on GDP per capita and the possibility of future government policies undermining economic or fiscal strength -the latter weakening business confidence.