As 2026 approaches, Ghana appears poised for a rebound in economic growth. Recent data and forecasts suggest improving macroeconomic stability, recovering investment, and renewed external confidence. However, structural vulnerabilities and global headwinds remain formidable.

Over the past two years Ghana has made meaningful progress toward macroeconomic stabilization, setting the stage for growth in 2026. After the steep inflation crisis that peaked in 2022, inflation has moderated significantly. According to recent data, consumer inflation has dropped to single digit, within the Bank of Ghana inflation target band of 8% ± 2%, in late 2025 following years of double-digit inflation.

At the same time, the external sector has strengthened. The completion of a major debt-restructuring exercise under the auspices of a funding program from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has improved investor confidence and allowed some fiscal breathing room. The IMF itself, following its most recent review, noted that global reserves accumulation has “far exceeded” its program targets, driven by robust exports of gold, oil, and other commodities.

Consequently, fiscal consolidation efforts appear to be bearing fruit. The government pushed for a 2025 primary surplus of 1.5 percent of GDP, which was achieved through a mix of revenue enhancements and spending rationalization, including tighter controls over payables accumulated in 2024. The improved debt-profile is expected to continue: some forecasts predict that Ghana’s debt-to-GDP ratio will decline in 2026 relative to 2025.

Tighter monetary policy and stabilization efforts appear to be bearing fruit. In this context, 2026 could see inflation maintain the single-digit range, especially if food-price pressures ease and exchange-rate stability persists.

A stable currency and manageable inflation would help restore real incomes, encourage consumption, and lower the cost of borrowing, all of which are critical for boosting domestic demand and encouraging investment.

Fiscal Balance, Debt, and External Position

Public finances remain under pressure, but recent reforms are slowly re-establishing stability. According to the AfDB, Ghana’s fiscal deficit is expected to shrink to 3.5% of GDP by the end of 2025, with further narrowing to 3.0% in 2026 under continued fiscal consolidation.

Meanwhile, debt sustainability appears to be improving. The debt-to-GDP ratio — which soared during previous years of macroeconomic instability declined in 2025 and could continue downward in 2026 under disciplined fiscal management and improved domestic revenue mobilization.

On the external front, exports, particularly from mining (gold, minerals) and oil — combined with better trade balances and reserve accumulation, provide some cushion. The AfDB foresees a positive current-account balance of 2.6% of GDP by the end of 2025, narrowing to 1.4% in 2026. This external stability is essential to support the currency and maintain import cover, especially as the country seeks to re-access debt markets and attract foreign investment.

Why 2026 Could Be a Takeoff Year

The improving growth–inflation–fiscal balance triangle is perhaps the most encouraging indicator. A rebound in GDP growth from 5.7% in 2024, paired with moderating inflation and a declining debt-to-GDP ratio, suggests that the worst macroeconomic turbulence may be behind Ghana.

Lower inflation, in particular, can restore consumer and investor confidence. For businesses and households, price stability means more predictable costs and planning. For investors — domestic and foreign — stable macro conditions reduce uncertainty, which tends to unlock investment and capital inflows.

Ghana’s long-term reliance on commodities such as gold, oil, and mineral exports remains. In a favourable global environment, for instance, strong gold and oil prices — these sectors can significantly boost foreign-exchange earnings, support the cedi, and improve the external account.

With debt burdens easing and reserves recovering, there is greater scope for Ghana to leverage its natural resource base, reinvest in infrastructure, and support industrial expansion. If mining and mineral output continue to perform strongly, they could play a key role in lifting the economy in 2026.

With macroeconomic stabilization and fiscal discipline, Ghana may attract renewed interest from foreign investors, international creditors, and development partners. A stable external position, clearer debt outlook, and manageable inflation would make Ghana a more credible investment destination.

At the same time, improved domestic conditions like lower interest rates (as inflation falls), better exchange-rate stability, and clearer fiscal management, may encourage domestic firms to invest, expand operations, and hire. This could trigger virtuous cycles of growth, employment, and private-sector-led development.

Economic Outlook for 2026: Growth Projections and GDP Performance

Ghana’s economy registered a robust growth rate of 5.7 percent in 2024, marking a strong rebound. For 2025, most institutions expect a moderation: the African Development Bank (AfDB) forecasts 4.5% growth. The World Bank recently revised its 2025 estimate to 4.3%, up from an earlier 3.9%. Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects 4.0% growth in 2025.

Looking ahead to 2026, several institutions are optimistic but cautious. The AfDB projects 4.8% GDP growth in 2026. The IMF also estimates 4.8% for 2026 under its programme assumptions. The World Bank’s medium-term outlook points to 4.6% growth in 2026 and increasing further to ~4.8% by 2027.

These projections suggest a moderately strong and steady expansion— enough to deliver real gains in output, employment opportunities, and investment, if underlying conditions hold.

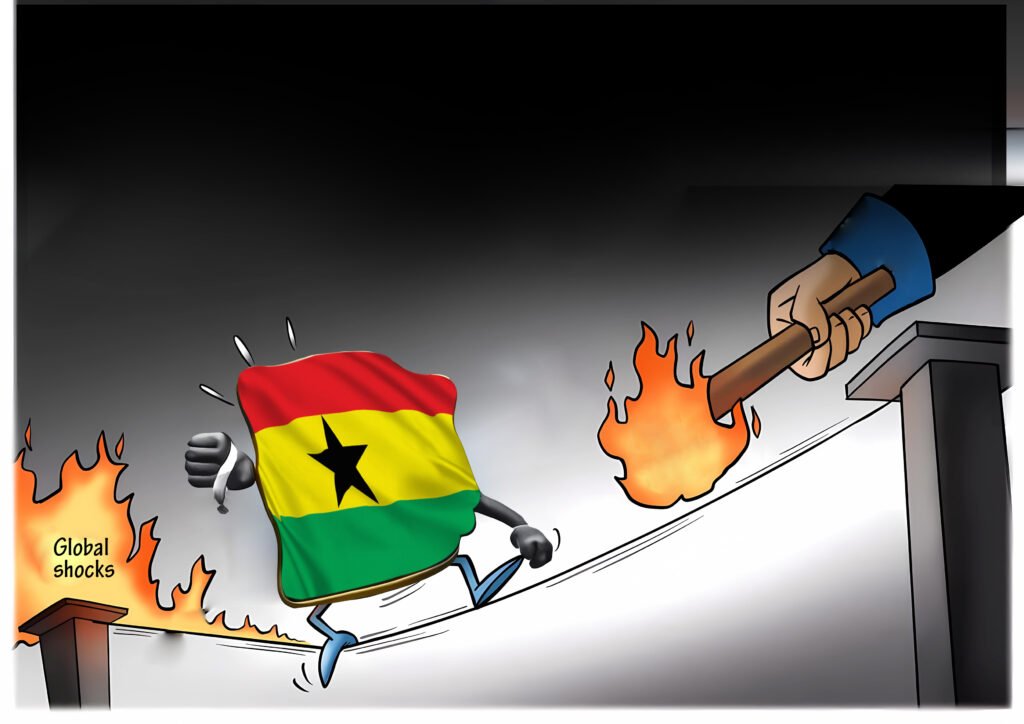

Major Threats to the 2026 Upswing

Ghana’s external strength still depends heavily on commodities — gold, oil, and minerals. Global commodity price-swings remain outside Ghana’s control. If gold or oil prices drop, export revenues, foreign reserves, and the broader external cushion could shrink rapidly.

Such a drop would hurt the external account, reduce foreign-exchange inflows, and potentially weaken the cedi. That, in turn, could reintroduce inflation pressure and undermine the hard-won macro stability.

Moreover, global economic uncertainty is a major risk. If major economies slow down, demand for commodities could drop, affecting Ghana’s exports. Global interest rate dynamics, especially if advanced economies keep rates high, could make external financing more expensive or hard to secure.

Tighter global liquidity can reduce capital flows to emerging markets, including Ghana. This could deter foreign direct investment (FDI), strain external financing needs, and weigh on economic expansion.

Geopolitical risks, supply-chain disruptions, or changes in trade policies worldwide could also negatively impact commodity demand or export logistics, further jeopardizing Ghana’s external resilience.

Structural Weaknesses at Home: Debt Vulnerabilities, Fiscal Slippages, and Sectoral Fragilities

Although the debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to decline further, public debt remains high. The sustainability of that decline depends heavily on fiscal discipline, continued revenue mobilization, and prudent expenditure. Any reversal such as new large spending, adverse shocks, or external revenue shortfalls, could quickly undo progress.

Domestic structural issues remain intact. Credit growth remains weak, and private-sector credit remains constrained. Without strong credit flow, private investment, manufacturing expansion, or SME growth may be limited.

Moreover, critical sectors such as agriculture remain vulnerable to climate shocks, pest outbreaks, or adverse weather. Given Ghana’s reliance on cocoa and other agricultural exports, climate-induced yield losses could upset export earnings, food prices, and economic stability.

Finally, the energy sector’s fragility (infrastructure constraints, supply reliability, cost of energy) may limit industrial expansion critical for diversification beyond extractives.

Again, riding on commodity export strength and favourable external conditions might deliver short-term growth spikes, but without structural transformation, the underlying vulnerabilities remain. If policy focus is on stabilizing macro indicators rather than diversifying the economy, Ghana runs the risk of repeating past cycles of boom and bust tied to commodity cycles.

Sustainable long-term growth requires investing in manufacturing, agro-processing, ICT, services, and building resilient domestic export capacity — a transition that requires sustained political will, regulatory reforms, and investment in infrastructure and human capital.

Policy Direction

To break the dependence on commodities, Ghana must actively invest in, and incentivize, value-adding sectors. Agro-processing, light manufacturing, consumer goods, building materials, and ICT represent viable areas for diversification.

Investments in infrastructure such as roads, ports, energy, reliable power supply, transport logistics will lower production costs, improve efficiency, and attract both local and foreign investors. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) and streamlined regulation can help.

Promoting SMEs and supporting them with credit, technical assistance, and linkages to export value chains could help boost domestic production, job creation, and reduce reliance on raw export commodities.

Continued fiscal consolidation is essential. The government must avoid reverting to heavy spending or accumulating new arrears. Transparent budgeting, timely audits, and prudent expenditure prioritization will help keep the deficit and debt ratio under control.

Revenue mobilisation should be improved through tax-base widening, better compliance, and non-debt financing for capital projects. Reliance on volatile commodity revenues for recurrent expenditure should be minimized.

Building Resilience Against External and Climate Shocks

Given the volatility of global commodity prices and climate risks, Ghana should build buffers: maintain foreign-exchange reserves, stabilize the exchange rate regime, avoid excessive external borrowing, and build strategic food reserves.

In agriculture, investments in climate-resilient farming practices, irrigation systems, improved research, drought-resistant crops, and sustainable farming methods are required. Diversifying crops and promoting agro-processing can reduce vulnerability.

Upgrading the energy sector, improving infrastructure, ensuring reliable power supply, encouraging renewable energy adoption, can reduce production costs and increase industrial competitiveness, supporting diversification.

The government should improve the investment climate. That requires enforcing contracts, ensuring regulatory clarity, protecting property rights, and ensuring timely servicing of public debt and arrears.

Credit growth should be encouraged: improving financial sector health, reducing non-performing loans, and fostering financial inclusion will help channel domestic savings into productive investments.

Attracting FDI will require stable macro conditions, transparent policy, and investor-friendly regulation. Ghana’s recent stabilization offers an opportunity — but only if the authorities maintain consistency, follow through on reforms, and deliver on commitments.

2026, A Critical Inflection Point

If Ghana achieves the growth, inflation, fiscal, and external-account benchmarks projected for 2026, ~4.8% growth, stabilizing inflation, narrowing deficit, declining debt-to-GDP ratio, and healthy export performance, it may signal a structural turning point.

Such a trajectory would shift Ghana away from crisis-driven economic cycles and toward a more stable, diversified, and investment-friendly economy. For citizens, that could mean more jobs, stable prices, improved investor confidence, and better long-term prospects.

But if the country fails to address structural weaknesses such as overreliance on commodities, weak private sector financing, inadequate diversification, climate vulnerability, then 2026 could become another cyclical high before a new downturn.

In effect, 2026 offers a narrow window for Ghana to convert short-term gains into long-term economic transformation.

In the intervening time, Ghana enters 2026 with cautious optimism. Economic forecasts from major institutions paint a picture of reasonable growth, improving public finances, and potential macroeconomic stability. These positive signals, if sustained, could mark the beginning of a new growth era.

Yet optimism must be measured. The legacy of debt, structural economic weaknesses, dependence on volatile commodity exports, and exposure to global and climate shocks remain. For Ghana to truly ‘jet-off’ rather than just bounce back, 2026 must be used as a springboard: a year in which policymakers, the private sector, and stakeholders commit to long-lasting structural reforms and diversification.

If that happens, Ghana’s economy may finally transition from cyclical vulnerability to stable, inclusive growth. If not, the promises of 2026 risk fading with the next global shock.