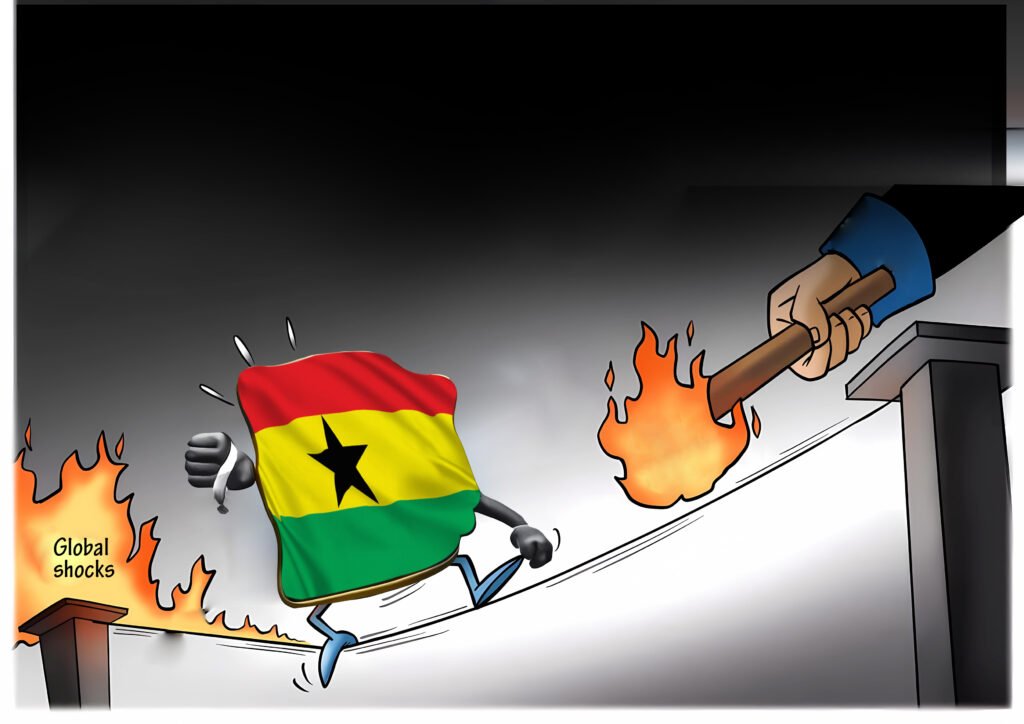

Fondly called “The Asempa Budget” but with the goal of “sowing the seeds for growth and jobs”, Ghana’s 2017 budget was broadly received with a vote of confidence and a sigh of anticipated relief for businesses and individuals.

Given that only three expenditure items on government budget (employee compensation, interest payments and grants to other government units) consumed 99.6% of total revenue for the 2016 fiscal year, there is little doubt that the new government had its work cut out. The need for fiscal space cannot be overemphasized as government revenue had been virtu- ally crowded out from capital and other critical investments.

The real growth rate in the Bank of Ghana’s Composite Index of Economic Activity, CIEA, (a proxy for business and consumer confidence) declined sharply from +4.1% at FY-2015 to -2.3% at close of 2016.

The real growth rate in the Bank of Ghana’s Composite Index of Economic Activity, CIEA, (a proxy for business and consumer confidence) declined sharply from +4.1% at FY-2015 to -2.3% at close of 2016.

Actually, the real growth rate for the CIEA nosedived into negative territory throughout the last quarter of 2016, reflecting the lowest points for business and consumer confidence and the urgent need to ease the punitive regime endured by investors. Given the pressing need to ease the operating environment for businesses, the government’s gesture of tax reliefs amidst the prevailing fiscal constraints resulted in an upturn in investor confidence. During the 2016 elections, one of the economic philosophies of the New Patriotic Party’s (NPP) manifesto was based on “switching from taxation to production”, supported by the belief in the private sector as the engine of growth. The decisive victory for the party could therefore be viewed as an overwhelming endorsement of a change in Ghana’s fiscal direction, underpinned by the crucial need to restore investor confidence in the country’s prospects.

Switching from Taxation to Production: Appears consistent with the IMF’s views expressed in the Fiscal Monitor published in April, 2017

In its latest publication of the Fiscal Monitor (in April, 2017), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) insists that three main objectives should guide the conduct of fiscal policy. Although limited fiscal space (in the Ghanaian case) and possible trade-offs poses a constraint to government’s ability to simultaneously pursue all three objectives, the 2017 budget represents a major step in alignment with the IMF’s views. Two out of the three main objectives of fiscal policy as espoused by the IMF includes the following:

Fiscal policy should be countercyclical: A countercyclical policy is one that moves in opposite direction to the business cycle being experienced by the country. In other words, fiscal policy should expand in bad economic times and tighten in good times in a symmetrical order to ensure automatic stabilizers around the cyclical swings of the economy. The fiscal tightening in good economic times would allow the government to build fiscal buffers

to support expansion in bad times. The IMF however argues that commodity exporting countries (such as Ghana) which have suffered significant fiscal shocks would require fiscal tightening regardless of the cyclical conditions in order to ensure fiscal sustainability or restore investor confidence. The counter argument in Ghana’s case is however based on the Laffer curve which stipulates that there is an optimum tax rate at which government revenue is maximized and beyond which revenue mobilized begins to fall.

From all indications in the 2016 fiscal data, it appeared Ghana’s tax regime had become punitive and was undermining government’s efforts to restore fiscal space through continued tightening of the fiscal regime. This therefore provides a case in favor of easing the tax regime to redirect productive capital into the private sector to support business expansion and ultimately higher government revenue in the medium term.

Fiscal policy should be growth friendly: Fiscal measures can be used as structural instruments to support the three engines of growth: the stock of physical capital, the labor force and productivity. According to the IMF, more growth-friendly business tax systems that focus on taxing rent-seeking and reducing burdensome tax administration practices can promote private investment. With respect to productivity, a range of policies, including tax incentives, can foster innovation that reduces the misallocation of resources across firms and boost business productivity and growth. According to the IMF, countries can reap substantial productivity gains by reducing resource misallocation which results from poorly designed government policies that allows less efficient businesses to gain market share at the expense of more efficient ones.

Tax Cuts and Reductions: Implications for Government’s Fiscal Operations

There is no doubt that the tax incentives announced in the 2017 budget and currently being implemented would impose some revenue loss on the government in the current fiscal year. Essentially, government’s cash flow from taxes could be exposed to the “J Curve” phenomenon where revenue inflows would experience a short term decline before recovering in the medium term as businesses begin to declare improved profits.

In the short term, the raft of tax cuts and reductions are expected to result in a GH¢1billion revenue loss to the government, raising the potential for the “J Curve” phenomenon if strict expenditure rationalization measures are implemented. According to the Bank of Ghana, provisional data on government fiscal operations in the first quarter of 2017 showed a shortfall in total revenue compared to the target for the period requiring strict expenditure rationalization to contain the fiscal risks. Total revenue and grants for the first quarter of 2017 was GH¢8.34 billion (o/w GH¢6.71 billion was tax revenue), representing a 14.5% shortfall relative to the target. However, strict expenditure management ensured that total expenditure and arrears clearance for the first quarter of 2017 (GH¢11.39 billion) remained below the budget limit of GH¢12.81 billion. While it is worth noting that the first quarter of 2017 was not captured in the tax cuts announced in 2017 budget, the revenue shortfall for the period raises the need to sustain the strict enforcement of expenditure rationalization measures to contain potential fiscal risks. The potential loss of GH¢1 billion indicates that government must ensure leakages and non- compliance to administrations are reduced to compensate for the losses due to the tax cuts.

The potential savings from a substantial reduction in tax exemptions could rake-in sufficient inflows to minimize the fiscal risks of the tax cuts. Revenue losses due to tax exemptions have been estimated at about GH¢2.4 billion, out of which about GH¢1 billion is due to unbudgeted tax exemptions and imposing significant revenue shortfalls on the government. Government’s capacity to significantly limit tax exemptions and reduce revenues losses would compensate for the tax incentives and also limit the fiscal risks. The strict enforcement of the Public Financial Management (PFM) Law passed in 2016 and implemented of the Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS) would also ensure and enhance the transparency and credibility of the fiscal framework, limit the expenditure risks.

Broadening the tax base and ensuring compliance would also boost the revenue stream in the medium term. Government’s quest to deploy electronic point of sales (POS) devices, the Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN) System and the National Identification System are laudable means by which the tax base can be broadened over time. An audit of the tax payers register and companies registered in Ghana would also reveal businesses that do not file their tax returns and this would increase the scope for more revenue stream in the medium term.

Tax Cuts and Reductions: Implications for Businesses in Ghana

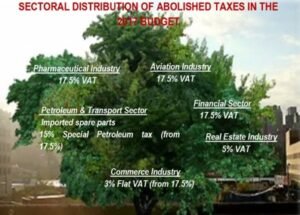

The tax incentives in the 2017 budget are expected to stimulate businesses investments in various sectors of the Ghanaian economy. The sectors include: the petroleum and road transport sectors, the aviation industry, the financial sector, real estate sector, pharmaceutical industry as well as commerce sector.

With an estimated GH¢1 billion loss to government as a result of the tax incentives to various sectors of the economy, this could be equivalent to a stimulus or aggregate capital injections of the same amount into the Ghanaian economy. In the short to medium term, the multiplier effect of this “stimulus” should boost productivity, overall GDP growth and aggregate demand. Ultimately, the anticipated growth in business productivity and profitability should boost direct and indirect tax inflows to the government over time.

While the government has abolished the 17.5% VAT on selected imported medicines not produced in Ghana, a policy to restrict the importation of selected list of medicines commenced in December 2016 and is to be enforced in 2017. The latest indications are that a list of 49 medicines would no longer be imported, allowing supply gap to be filled by manufacturing companies in Ghana. According to the Ghana Chamber of Pharmacy (GCP), the local pharmaceutical manufacturers account for only 30% of an industry estimated to be worth GH¢1.36 billion as at 2016. This indicates the opportunity for expansion in local manufacturing capacity given the availability of market for the output.

In conclusion, the tax cuts and reductions is a step in the right direction and consistent with the new era of upgrading the tax administration system to stimulate economic growth rate above the baseline model. However, the process requires strict monitoring and efficient implementation in order to minimize the potential short term fiscal risks to Ghana’s economy as a result of the revenue forgone.